You could understand the language of the lagoon as you stepped out of your BMW and walked tearfully towards it. The water first began with a lullaby – a soft, sweet song that made your soul willing to sleep in the womb of the water. You listened. Your eyes were looking downwards, looking at the image of yourself in the water. That image that bound you to the lagoon and you saw how both of you fitted each other. You saw that you belonged here, right inside this water. You could see the water washing away the pain and bitterness eating your heart. You could see it as it whitened your skin and filled the whole of your body. You would become a swollen, white entity that had found peace after this water would have sailed away your soul.

A boy wearing brown shorts and no top, rolling a canoe snatched you away from the vision in the eye of the lagoon. The boy should not be older that your twelve year old son, Keem. Keem died three hours ago. Keem, your only son, the pillar of your pride after your husband, his father, died three years ago in a fatal car accident, actually died three hours ago. He was your second husband. Now your husband was dead again. Twice dead!

The boy became Keem. The metamorphosis started with his face, then his whole body; the semi-nude boy was now Keem, dressed like him before his death, in his school uniform (blue and white striped shirt and a pair of navy blue shorts). At first, you thought your son was alive. You wanted to jump into the lagoon and go after him, even though you could not swim.

“Akeeeeeeeeeem!” You screamed your son’s name. But after some seconds, it was the boy again, staring at you, probably wondering who you were calling. He had seen too many women like you, so he was not surprised seeing you. He smiled and rolled away. You watched him decrease from a full human to a dot, then to nothing. All you could see now was water, water with a yawning mouth.

***

You were in your art studio when you received the call from Keem’s school.

“Madam, your son has started again o...” His class teacher informed you over the phone. You could perceive panic in her voice, the panic that glided into your heart and rolled itself into a ball, beating against your ribs as your heart beat.

You told Kore, a girl you were training to improve her drawing skills, that you would be back soon, and you ran outside. You had forgotten your scarf and car keys. You ran back inside to get them, looking like a woman that had broken free from Yaba Psychiatrist Hospital.

“Ma, any problem?” Kore asked, but your soul and mind were already out of your body and were at Keem’s school. She stared at you as you ran out the second time, wondering what was wrong with you, her art tutor.

After spending about thirty minutes in the Lagos traffic jam, you got to your son’s school. Some of his classmates, who were fanning him with their notebooks, surrounded your son that was gasping terribly for oxygen. Because Ebola was in Nigeria, most people stood away from your son, who was only asthmatic.

You searched his pocket and school bag for his inhaler, but you could not find it. Probably, he had forgotten it at home, or he had misplaced it. You lifted him into your hands and ran with him outside into your car. You put him in the backseat, closed the door and ran to the driver seat, telling him to hold on, that you would take him to the hospital and he would be fine. You wound down the windows for enough air to flow into the car, and you zoomed off. The class teacher ordered everyone into the class, and lesson continued as if nothing had happened some seconds ago.

You drove into the General Hospital, a place crowded with sick people left unattended to by the doctors and nurses. As you rushed into the hospital, people began to distance themselves from you. You rushed to a nurse.

“Please, em… help my son… em… he has… em… Ebola… No… no… no, I mean he is asthmatic o.” You were so confused and worried that you were not able to form your thoughts and words well. The only thing the people present there at the hospital heard was that ‘your son has Ebola’. Ebola, that contagious, deadly disease?

The nurse you approached moved away from you. No one wanted to come close to anyone with Ebola. Even you would not if you were in their shoes.

You moved back and forth, shouting for help, telling people there that your son did not have Ebola, but was only asthmatic. You tried to explain, but the word ‘Ebola’ had blurred out every other thing you had to say. Keem took a long breath, and breathed no more. And you left his body there.

“You have killed my son and you must bury him!” You shouted at no one in particular. And you walked away.

“Madam, come carry your pikin comot from here o. Security! Security ooo!” A nurse tried to make you carry your child, but you did not answer her. You matched out of the hospital into your car, and you drove off, leaving behind thick fumes.

***

You became conscious of the voice of the water again. This time it was not singing, but speaking to you, telling you how beautiful and peaceful death is, telling you how it would wash away all the pain and bitterness you felt, telling you that it would take you home to your husband and son, that you would live happily ever after in its arms.

But you remembered an essay you wrote in SSS3. Your English, Mrs Jumo, had asked the class to write an essay on how you want to die. She gave your class the assignment after she lost her husband. One thing everybody in your school observed was that Mrs Jumo did not show any sign of sadness or mourning. She still taught her class cheerfully. There was even a rumour that she might have killed her husband, but no one could give a reason why she might have killed him.

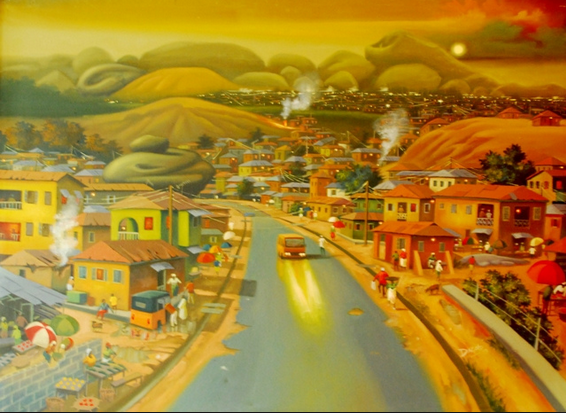

Anyway, you remembered everything you wrote in that essay. You wanted to die an art genius after you had done not less than ten art exhibitions. You had imagined your paintings taking you round the world. You dreamt to be as great as, or even greater than, Suzanne Valadon, Felicia Browne, Marie Laurencin and Mary Cassatt: all these female artists and many more inspired you. All you wanted was to be a successful artist before you died so that the world would pause and mourn on the day you die.

So far, you had done two art exhibitions, and travelled to only Ghana and South Africa. Next month, you were to go on a tour to seven African and European countries to display your artworks. But if you jump into this water now, your dream would have to die at dawn.

So, you thought twice. This was not the kind of death you envisioned for yourself.

“No, I can’t die like this. I must be hopeful and live on for hope is the lubricant of life. I can remarry and have a child or more. I can even adopt a child. No, I just can’t give up now. I know I still have something to offer the world.” You tried to motivate yourself.

“Perish that thought, woman. Your life can never be the same again. No matter how long a zebra bathes in a river, it cannot wash away its black stripes…” The lagoon spoke to you, urging you to jump into its open mouth.

But you turned, walked back into your car and drove off. You would go to the hospital, pick your dead son and bury him. Then you would live life afresh. You promised yourself not to give up so soon. You deserved more, more than what death could offer. And you continued driving into a new life.

Writer’s Bio: Samuel Oluwatobi Olatunji is a freelance writer and editor. He has been published in a number of journals, magazines, anthologies and blogs such as Black Heart Magazine, Black Communion (Poets of the New African Poets), Rolling Thunder Quarterly, Rivers Poets Journal, Footmarks: Poems on One Hundred Years of Nigeria’s Nationhood and elsewhere. He is the co-editor of The Rape of Death, an anthology of poems. Currently, he is studying English at University of Lagos, Nigeria. You can follow him on Twitter: @Mr_Samitude

1 comment

Deep!!! Pain makes us want to do insane things, I can totally relate!!!